The mystery of the non-traumatic injury

A traumatic injury, though devastating, feels slightly more comprehensible than its counterpart. If a car hits you, or you fall off your bike, the reason why you’re in pain is clear. A non-traumatic injury could be a sore lower back, a painful neck or an immobile hip, with no clear triggering event. They fall into all kinds of categories; overuse injuries; chronic restrictions; biomechanical blocks; the single unifyer being no set cause or solution.

Doctors typically refer this type of issue to a physiotherapist. Though physiotherapy approaches are highly varied, it is popular to treat each limb and joint isolation; if the groin is tight, one might prescribe adductor strengthening exercises; if the shoulder is stiff, it’ll be shoulder band exercises. Research since the turn of the century is encouraging physios to take on a more integrated interpretation of the body.

What if localised pain comes from global dysfunction?

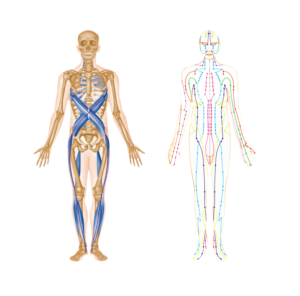

In 2008, Tom Myers popularised the idea of anatomy trains in Western thought. Myers explains how muscles don’t work in isolation, they operate in long, continuous fascial chains. This reframes movement, posture, compensation, and pain as whole-system behaviours.

This interpretation is something that has been widely accepted in the East for over two-and-a-half-thousand years. The ancient school of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) teaches its students that the body is a network of meridians – functional routes that deliver feeling, pain and energy through the body. If these pathways become blocked, pain can be felt anywhere along the chain – the same is true of Myer’s anatomical trains.

Anatomy Trains (left) and TCM Meridians (right)

How this should inform self-rehabilitation

What to do with the idea that non-traumatic pain is deferred can be perplexing. Trying to map the cause onto another body part can leave you in a perpetual (and frustrating) game of guesswork. Crucially, this approach still falls prey to the idea that one specific area is the sole cause of the dysfunction.

Instead, alleviating pain should be approached in the context of improving the overall health of this body network that has been identified by both Eastern and Western researchers. A network which, in a physical sense, is held together by connective tissues, or, fascia. Understanding the properties of fascia could be the key to unlocking a more effective healing process.

A dive into fascia and how to improve it

In a literal sense, fascia is the glue that holds your parts together – if you’ve ever prepared meat in the kitchen, fascia is that sticky white web between the chunks of muscle. In a body that moves fully, fascia is mobile and flexible; in a body that doesn’t, the fascia thickens (dehydrates) which sets in the immobility by restricting the muscles that it encapsulates. So, revitalising this network involves rehydrating the fascia, which occurs through the gradual reintroduction of functional movement. That kind of movement most of us had as kids.

Perhaps the most relevant property of fascia to this inquisition is that it remodels much, much slower than muscles. Some studies find that meaningful structural remodelling can take 6 to 24 months. Brendan Backstrom, the man behind the cult low back rehabilitation movement LBA, stresses this idea that tissue adaptation involves incremental gains over a prolonged period of intentful training. Backstrom’s online community commits to years of functional training.

Conclusion

Unexplained pain is usually a sign of a wider system dysfunction, and rehabilitation programs should consider this. A dive into the properties of the human fascial network reveals truly priceless findings in the quest for pain-free living. Firstly, healing fascia is an engaged process steered by the patient not the practitioner. No practitioner can solve chronic pain the way a cast can fix a fracture – healing requires intentful proaction on the part of the patient. Secondly, improving tissue tolerance is an extremely slow burner. Instead of seeking an overnight fix, digest the idea that this dysfunction has been layering over years and will take years to unravel. So lock in, take a long-term approach and celebrate the small wins.